Throughout your investment journey, it is likely that the maximum number of positions you would like to hold has fluctuated over time. But is there a sweet spot for the perfect number of positions?

In this article, I will cover what scientific research has to say about it and whether there is a perfect number of positions to hold if you are investing in individual stocks. Let me start with risk, because it is a crucial factor in determining that sweet spot.

What is risk?

When talking about “risk” in the stock market, most people think about the chance of losing money. But risk is not one thing. It is a mix of different forces that move prices.

At the highest level, there are two main types:

- Systemic (market) risk: the broad forces that affect nearly every stock. Think interest rate hikes, recessions, geopolitical shocks, pandemics. No amount of stock picking can fully escape these waves because they move the whole ocean.

- Idiosyncratic (company specific) risk: the factors unique to each business. A failed product launch, an accounting scandal, a leadership change gone bad. These risks can be reduced simply by owning more than one company.

Understanding this distinction matters, because it defines what diversification 1 can and cannot do for you.

How diversification works

The whole point of diversification is to smooth out the bumps caused by idiosyncratic events and reduce the possibility of permanent loss of capital. If one company disappoints but another exceeds expectations, the overall ride gets steadier.

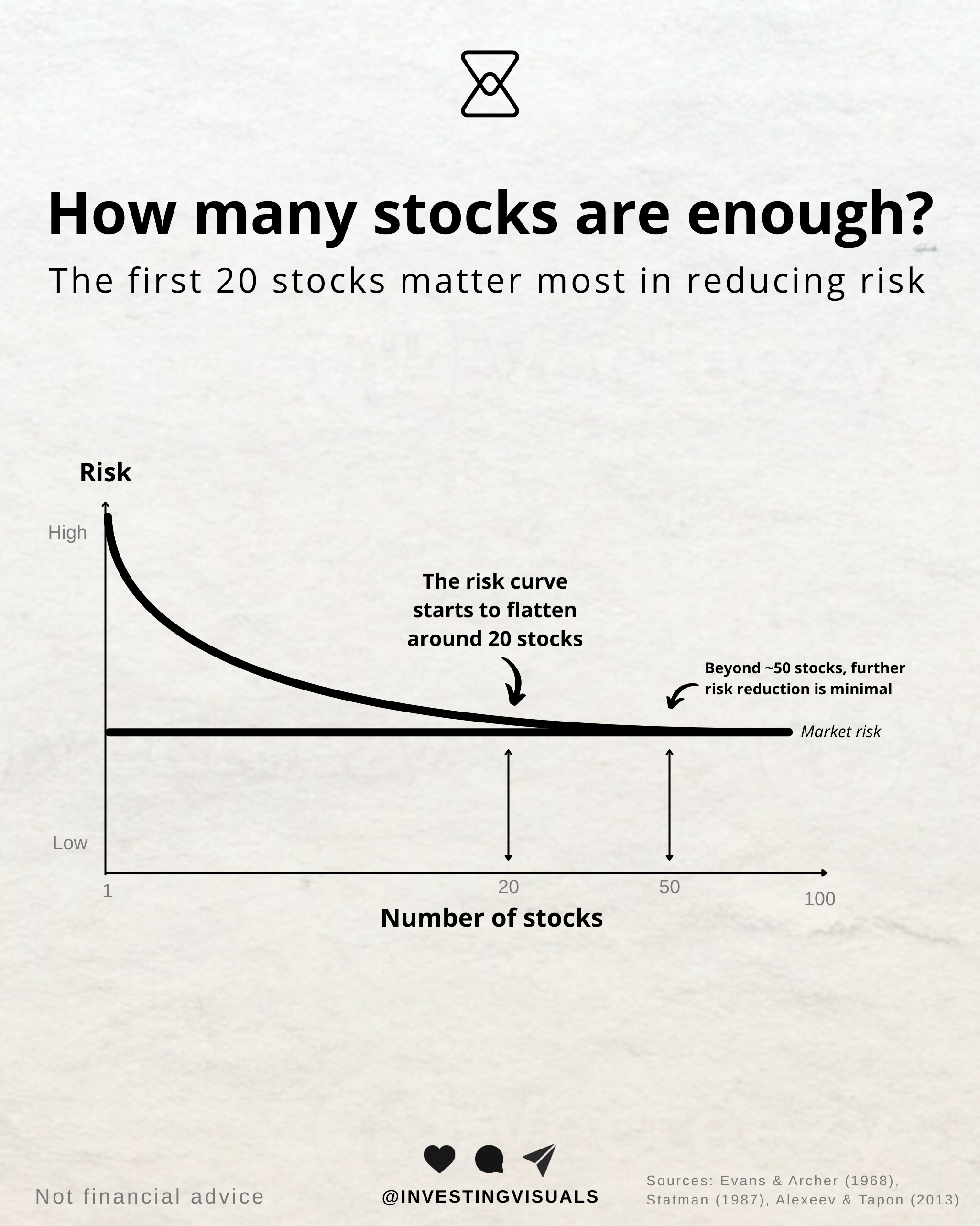

Now let us look at what research has to say. The relationship between the number of stocks you hold and the drop in idiosyncratic risk is not linear. It is a curve that falls fast at first, then flattens out.

Classic studies like Evans and Archer (1968) and the Elton and Gruber model showed that the biggest drop in risk happens within the first handful of stocks. Add 10 to 20 reasonably uncorrelated names and you have already diversified away most of the company specific risk. That is why the old rule of thumb says “20 is enough”.

More recent work adds some nuance:

- Statman (1987) found that to reach the same risk reduction targets investors used in his models, you often needed closer to 30 to 40 stocks.

- Alexeev and Tapon (2013) went further, testing across five developed markets and different risk measures. To reduce about 90% of diversifiable risk with around 90% confidence, they concluded you typically need around 40 to 50 stocks.

When looking at tail risk, the chance of a disastrous outcome or large shortfall over time, studies by Domian, Louton and Racine found there are still incremental benefits well beyond 50 stocks.

In short

Adding more stocks past 20 does continue to lower risk, but the effect becomes incrementally smaller with each extra name. None of this diversification touches systemic risk though. If the whole market drops, every stock feels it.

When more stocks stop helping

Research broadly agrees on three points:

- Diminishing returns: going from 1 to 10 stocks slashes risk. Going from 20 to 40 still helps, but far less. Going from 40 to 100 makes only a marginal difference.

- Correlation matters: if all your stocks sit in the same sector or move with the same factors, you are not really diversifying, so you might need more than 20 to get the same protection.

- Risk floor: there is always a baseline level of volatility set by the market itself. Diversification cannot lower that.

To summarize

Risk is the blend of market wide waves and company level surprises that can cause loss of capital. Diversification is your main tool against it, and it works fast at first. Most of the benefit shows up within the first 20 or so reasonably different stocks.

But research is clear: the curve does not flatten completely. It continues to decline gradually up to around 40 to 50 stocks. Beyond that, you are mostly just padding the edges.

Additionally, no portfolio size can diversify away systemic shocks. That is where asset allocation, cash buffers and your own risk tolerance come into play.

So how many stocks is enough? According to research, around 20 reasonably unrelated assets address the majority of company specific risks. My personal add to that would be that it also depends on the extent to which you are able to closely track all your positions.

My personal sweet spot

I used to have 25 positions at one point, but I was not able to follow all of them closely, which meant missing important signs of a deteriorating thesis for example. At the end of the day, it is very much a personal preference based on your risk tolerance and the time you have available to keep track of your positions. My personal sweet spot is between 10-13 positions, which balances concentration with diversification while still being able to closely track all positions.

As always, none of this is financial advice. It is my attempt give you more insights into topics like risk and diversification. Always do your own due diligence before making an investment decision that fits your own risk tolerance and time horizon.

Get the latest updates and news in your inbox

Member discussion